This post was originally published on Mongabay on October 1st 2020. It is a follow-up to a previous story I wrote for Mongabay last year.

- Woodlark Island lies off the coast of Papua New Guinea and is home to dozens of unique species and a more than 2,000-year-old human culture.

- A recent court ruling has seen the land rights granted to Woodlark islanders in 2016 revoked and returned to an agricultural company that in 2007 planned to transform 70% of the island into oil palm plantations.

- Meanwhile, the status of an application submitted to the PNG Forest Authority by a logging company to clear 40% of the island under the guise of an agricultural project remains unknown, despite an ongoing petition signed by more than 184,00 people.

- A mining company has also started expanding infrastructure and clearing forest in preparation for a long-planned open-pit gold mine, but has faced backlash from villagers unhappy with the replacement housing offered as part of a relocation project to make way for the mine. The company also intends to dispose of mining waste via a controversial pipeline into a nearby bay.

A unique rainforest island lying 270 kilometers (168 miles) off Papua New Guinea is once again at the center of a tug-of-war between multiple extractive industries vying for its rich natural resources. Woodlark Island is home to dozens of species found nowhere else on Earth, but faces numerous overlapping threats from gold mining expansion and looming potential agricultural and logging projects.

After a hard-won battle to regain customary land ownership over their New York City-sized island, Woodlark islanders recently faced a major land rights setback. A court has effectively revoked the islanders’ customary ownership over some 70% of Woodlark, returning the mostly forested area as a lease to Carter Holdings Limited.

The company, formerly known as Vitroplant Limited, was the driving force behind a thwarted attempt to establish a large-scale biofuel project on Woodlark in 2007.

Meanwhile, Woodlark still faces ambiguous threats from Malaysian-owned logging company Kulawood Limited, which has submitted a forest clearance application to the Papua New Guinean Forest Authority.

The forest clearance application covers 30,000 hectares (74,000 acres) — around 40% of the island’s forest — but its status is unclear. This is despite an ongoing petition signed by more than 184,000 people calling on the Forest Authority to halt the deforestation. A similar petition launched earlier this year garnered some 228,000 signatures.

An Australian mining company has also started expanding infrastructure on Woodlark. Geopacific Resources Limited, however, has been forced to halt a planned relocation project after locals rejected the living facilities provided by the company. The planned relocation is part of an attempt to move some 250 families from Kulumadau village to make way for a mining plant and open-pit gold mine.

Scientists worry this melee of developments will spell disaster for Woodlark’s unique biodiversity, and the thousands of people who call the island home.

An island like no other

Hopping onto Woodlark Island, the first thing a biologist might notice are the absences.

Gone are the colorful flashes and calls of birds-of-paradise, which have helped establish New Guinea as an ornithologist’s dreamland. They likely never reached the remote island. Gone too are the wallabies, the bowerbirds and a whole slew of other wildlife famous on the mainland.

Instead, Woodlark has its own set of evolutionary oddballs. There’s the Woodlark cuscus (Phalanger lullulae), a tree-living marsupial listed as endangered on the IUCN Red List that ekes out its existence in hollows, chewing on insects.

The island also has seven known endemic reptile species, seven plants, seven amphibians, two damselflies and a riffle bug, all found nowhere else on Earth.

As Fred Kraus, a herpetologist at the University of Michigan with expertise of the island’s fauna says, that’s a “lot of endemics for one small island.”

“The island is quite isolated and has been for several million years, so there has been no recent gene flow with relatives on the closest landmasses,” Kraus said.

Left to evolve in seclusion, the staggering diversity of Woodlark’s fauna is demonstrated perhaps best of all by an often overlooked group: its snails.

Woodlark’s snails flaunt a hodgepodge of psychedelic shell formations: some spiky, others smooth, all a fascinating natural experiment on the many ways to build a palace out of calcium carbonate.

A few have range sizes so small that of the planet’s 13 billion hectares (32 billion acres) or so of landmass, the only place they probably exist are in a few hundred square meters of Woodlark Island forest.

“Of the approximately 40 [species of] land snails I found on the island, about half are found nowhere else on the planet and half of these are new to science and are still awaiting formal description and naming,” John Slapcinsky of the Florida Museum of Natural History previously told Mongabay.

The lesson, shown to be true again and again on Woodlark Island, is that you’ll find new species if you just know how to look.

In 2016, scientists described a new frog from Woodlark in the journal Zooystematics and Evolution. They heralded it as a “striking new species of the microhylid frog genus Mantophryne,” and announced that, like the mineral deposits that run in the ground beneath its toepads, M. insignis had an eye-catching stream of gold running down its back.

Kraus also recently described a new species of gecko from Woodlark, Lepidodactylus kwasnickae.

“L. kwasnickae seems utterly dependent on the forest,” Kraus told Mongabay. “All of the endemics I know of are dependent on the forest habitat because that was the original land cover before humans came in and started clearing”

Yet much of this unique wildlife now faces an extremely uncertain future.

The return of an old enemy?

Back in 2007, Woodlark Island found itself at the center of local and international efforts to stop the wholesale destruction of its forests. The threat came after a Malaysian-owned company, Vitroplant, acquired a lease to develop a large-scale biofuel project on the island.

Vitroplant intended to clear 70% of the island’s forest (around 60,000 hectares, or 148,000 acres) to make way for a monoculture oil palm plantation, a move that scientists feared would cause spiraling extinctions among Woodlark’s unique fauna. The biofuel project sparked a firestorm of opposition at the time. This included fears from islanders worried about what sweeping deforestation and pollution would mean for their subsistence-based culture and the forests they depend on.

Following a global letter-writing campaign, targeted journalistic scrutiny and, most importantly, organized opposition from Woodlark Islanders, something very rare happened: the Papua New Guinean government put a halt to the project. The planned destruction of the island’s forest was thwarted. It looked like Vitroplant’s designs for Woodlark Island had been thwarted.

More than 10 years on, that no longer seems to be the case.

Vitroplant Limited’s Courtroom Manouverings

After changing its name to Carter Holdings, Vitroplant won a legal case to regain ownership of its former agricultural leases over large portions of Woodlark. The decision comes as a heavy blow to islanders, who have been fighting for recognition of their customary land rights for more than 50 years.

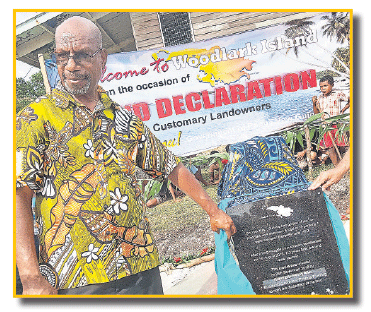

In November 2016, it seemed that Vitroplant’s claim on Woodlark was well and truly over, with islanders celebrating a landmark ruling by the national government, which appeared to finally recognize their land rights.

The ruling was announced by then-Prime Minister Peter O’Neill and was met by a joyous ceremony attended by residents from across Woodlark and surrounding islands, as well as government officials and visiting dignitaries. The minister of land at the time, Benny Allen, unveiled a plaque at the government station on Woodlark commemorating the occasion.

But that plaque now seems to have been rendered obsolete, and the islanders are once again facing a takeover of most of their island. For even as Woodlark’s inhabitants were celebrating the return of their customary lands, Carter Holdings had submitted a judicial review at Waigani National Court, claiming it still held the titles to three state leases on Woodlark, totaling 60,400 hectares (149,250 acres) of mostly forested area.

Then, on Feb. 22, 2019, the court ruled in favor of Carter Holdings to quash the designation of its former leases first as “government land,” and then as “customary land.” The verdict effectively restored Carter Holdings as the legal owner of some 70% of Woodlark Island’s land area.

Isi Henry Leonard, a member of parliament who represents Woodlark and the island of Samarai, has pushed to revive the case for customary land ownership on Woodlark. He says the court ruling came about because of a failure by government lawyers to push back against Carter Holdings’ claims.

“The Court did not take the evidence file by the Lands Department into consideration and only relied on the evidence [of land ownership] presented by Carter Holdings Limited,” Leonard said during a televised meeting in 2019.

He said he’s worried what the repeal of customary land rights will mean for Woodlark’s residents, who could now be sidelined by any future projects on the island.

“Carter Holdings will be the major beneficiary [of any future projects] because of the fact that they have the lease,” Leonard said. “And the landowners? Forget about it. If ever they sign an agreement between the state and the company, it will have no direct meaning to the people of Woodlark, even though they are landowners. They will be sidelined. They will be signing an agreement that will never affect their lives.”

But what kinds of projects are at play on Woodlark Island?

A tangled web of plans to clear a rainforest island

It’s unclear whether Carter Holdings intends to revive its 2007 bid to develop an oil palm plantation on Woodlark Island. Mongabay tried to reach Carter Holdings for comment, but contact information for the company is not publicly available.

Luke Petai, who grew up on the island, says he’s not aware of any current planned agricultural projects, but that “it is quite difficult to know of plans as in most cases, it is not discussed until when everything is set for operations … that is when we know of those plans.”

Previous assessments by the Department of Agriculture have also shown that soil suitability for oil palm across Woodlark is very low — though this has largely not prevented the expansion of oil palm in many similarly ill-suited areas of Southeast Asia.

It’s also unclear how Carter Holdings’ lease interacts with the web of intentions of other extractive industries crisscrossed around the island.

Woodlark already houses an expanding gold mine, which is the main employer for islanders and seems to fall outside of Carter Holding’s leases. But Woodlark has also recently been the focus for another Malaysian-owned company, Kulawood.

As Mongabay reported last year, Kulawood previously submitted plans to clear-cut 30,000 hectares of forest on Woodlark, an act scientists warn would destroy the island’s forests and doom many of its endemic species.

Kulawood reportedly intends the planned forest clearance to be part of a wider agricultural project called the Woodlark Integrated Agriculture and Forest Plantation Project. The company says it plans to plant a mixture of rubber and cocoa trees that will benefit locals after the deforestation.

However, a four-part series led by investigative outlet PNGi in 2018 found that Kulawood’s forest clearance application was “riddled with errors, inconsistencies and false information.”

What’s more, PNGi discovered that the company’s local partner, which is tasked with implementing the project, was granted approval by the Department of Agriculture in March 2017 despite having no previous experience with logging or agricultural development, no registered assets, and no staff.

Sources say this points toward a potentially illicit attempt by Kulawood to use agricultural development as a ruse to mask industrial logging operations on the island, which still has large stands of slow-growing ebony hardwoods. Such ruses are not unique to Woodlark, with companies routinely using agricultural loopholes to get around Papua New Guinea’s logging restrictions.

Despite an ongoing petition now signed by more than 184,000 people asking the PNG Forest Authority to cancel the project, the status of Kulawood’s forest clearance application remains unknown. Neither Kulawood nor the Forest Authority responded to Mongabay’s attempts to contact them.

However, it is now clear that should Kulawood’s logging plans proceed, a large part of its activities would have to fall within the leases returned to Carter Holdings.

Gold mining and the relocation of Kulumadau village

Meanwhile, longstanding efforts to expand gold mining are underway on Woodlark and facing controversies of their own.

Australian mining company Geopacific Resources announced in October 2019 that it had succeeded in raising $40 million in financing to begin preparation of multiple open-pit gold mines on Woodlark.

Photos and announcements on Geopacific’s website show that by February 2020, it had landed machinery on the island and started clearing plant sites as well as constructing more than 4 km (2.5 mi) of new roads.

Geopacific also began plans to relocate around 250 families from one of the island’s most densely inhabited villages, Kulumadua, which is located on a major gold prospecting site.

In 2019, Ron Heeks, Geopacific’s managing director at the time, said that the company had “made a commitment to engage as many Woodlark residents as possible for all aspects of the project, including the Kulumadau relocation.”

Yet in June 2020 Geopacific halted the relocation and Heeks allegedly was forced to resign after reports surfaced that the company failed to provide adequate housing alternatives for some 1,500 displaced residents.

“These kit homes are no match to our local homes built with bush material,” Bosco Lapis, a spokesperson for the Woodlark relocation committee, told a local news outlet.

Lapis said certain house designs consisted of only a single room, were not equipped with enough water storage facilities to sustain a family’s weekly usage, and were built with materials that locals would not be able to source and maintain once the mining company left the area.

Geopacific has since ceased the construction of the smaller dwellings and is in discussions with the Mineral Resources Authority (MRA) of Papua New Guinea and the Woodlark community to resolve the dispute.

Former islander Luke Petai, however, said not all locals feel they are being properly consulted about or compensated for the relocation by Geopacific.

“For the general local people including ordinary members of Dal Wanuwan” — a local landowner group that deals with the developer — “from what I am hearing from home, they have not been properly consulted,” Petai told Mongabay via email. “Therefore they feel they are not compensated properly.”

The company also faces growing scrutiny around its plans to dump toxic mining waste, called tailings, into the ocean. The proposal has attracting mounting criticism across New Guinea, particularly in the wake of recent disastrous pipeline spills at the Ramu nickel mine on mainland PNG.

Geopacific has previously attributed the decision to dispose of mining waste offshore to high rainfall and tectonic activity on the island.

David Mitchell, director of Eco Custodian Advocates, said safer alternatives exist, including lining mine pits with impermeable barriers then backfilling the waste within these pits. But Mitchell said he doesn’t believe the company seriously considered this option during its environmental impact assessment.

“I seem to recall that it was deemed too expensive,” Mitchell told Mongabay. “Yet in a multi-pit mine it would be an environmental best practice with a lesser environmental footprint.”

The impacts of deep-sea mine tailings disposal on ocean life remains mostly unknown to scientists due to the difficulty of surveying such environments. However, a paper published in Scientific Reports in 2015 found that large-scale dumping of gold mine tailings had severe impacts across the web of deep-sea marine life on nearby Misima Island.

Geopacific did not respond to Mongabay’s requests for comment.

What now for Woodlark?

“To us, the forest and the surrounding environment is a lifeline,” Petai said. “It holds our cultural heritage, the source of our living and is the platform of interactions for past, present and future generations.”

The island’s forests are a lifeline for its wildlife, too. Kraus says wholesale forest conversion would “consign scores of species to extinction.”

He said he’s especially worried by the potential for widespread clearance within Carter Holdings’ agricultural leases, since these contain the remaining portion of the island’s forests.

“Of the 25% of the island not in lease, virtually all of that would be unforested too because the local inhabitants would still have to make their subsistence gardens, and the disturbed land around the government station at Guasopa takes up a large portion of the remaining land,” Kraus said.

Gold mining poses a lesser threat to the island’s wildlife because of its smaller land footprint. But critics fear its impact on the island’s culture and offshore marine ecosystems could be disproportionately large.

Historic gold mining on nearby Misima Island proved something of a mixed blessing for islanders, according to Jordan Haug, a visiting professor of anthropology at Brigham Young University who recently carried out fieldwork on Misima.

“While it has increased people’s access to consumer goods, that increase has not been equal,” Haug told Mongabay via email. “Some Misimans have watched their neighbors prosper, while they do not. This has caused a lot of social tensions on the island.”

For now, a fog of uncertainty lies over Woodlark, buffeted by a trifecta of overlapping threats from gold mine expansion, logging, and industrial agriculture. The future of the island and its human and non-human inhabitants teeters on a small number of decisions and actors.

The legal battle over returning customary land ownership to Woodlark Islanders is on its way to the Supreme Court.

The Kulumadau village relocation plan and further gold mine expansion await the go-ahead from the Mineral Resources Agency.

Kulawood’s forest clearance application lies in the hands of the PNG Forest Authority.

And as for the possibility that Carter Holdings may revive its 2007 oil palm aspirations, Luke Petai has a warning.

“The company knows very well of the opposition from educated locals from the island since 2007,” he said. “If there [are] any plans, it will not go unnoticed.”